Clever Vegans Supplement B12

By Tobias Sjösten

Are you a vegan who doesn’t supplement vitamin B12? I strongly urge you to reconsider or the consequences can be quite serious.

Everyone needs a constant source of B12, whatever their diet. Vegans should pay extra attention to this but just because you’re eating someone else’s flesh doesn’t automatically mean you’re safe.

Summary: Vitamin B12 deficiency is a real threat, especially for vegans. The ramifications can be severe and we should take precautions not to run the risk of becoming deficient. Luckily, it’s very easy to avoid. Pop a cheap 500 µg B12 pill (cyanocobalamin) pill once per week or 50 µg once per day and you’re good.

Depending on who you ask, you need different amounts of the vitamin.

The American NIH recommends 2.4 µg vitamin B12 per day (2.8 µg for nursing mothers), while Brittish NHS recommends 1.5 µg, and the NNR 2012 recommends 2 µg.

That’s roughly three micrograms – three millionth of a gram. Quite small quantities but as we’ll see it’s a bit more complicated than chugging a pill with 3 µg of B12 and call it a day.

What they all agree on, however, is that you should make sure you get enough vitamin B12.

Won’t happen to me

Should you care though? What are the odds you’re affected?

One study showed that 39% of the general population may be low or deficient in the vitamin – vegans and carnists alike. Interestingly, it also showed that meat is one of the worst sources of B12.

Another study found that only 1% of patients with clinically expressed vitamin B12 deficiency were vegans. The other 99% were omnis!

Luckily, whatever your diet is there are simple solutions to meet your B12 needs.

What is vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12 (or cobalamin) is vital for your brain and nervous system’s function, as well as the formation of red blood cells. It has a key role in the metabolism of pretty much every cell of your body, in particular DNA synthesis, fatty acid, and amino acid metabolism.

It works as a coenzyme – enzymes uses it to do their job, changing one molecule into another.

The cobalamin molecule of B12 exists in many different structures: cyanocobalamin, methylcobalamin, adenosylcobalamin, cobamamide, dibencozide, hydroxocobalamin, etc.

No plant, fungi, or animal (humans included) are able to produce vitamin B12. Instead we have to rely on microbes for its synthesis. Bacteria in our colon can produce it but it happens so late in the intestines that we can’t absorb it. Instead we need to find other sources.

The good old days

Back in the days our food and water was a lot more contaminated than it is today. With the advent of clean water we’ve stopped many awful diseases from being spread but at the same time we’ve also removed reliable sources of vitamin B12.

People living close to animals in more unhygienic conditions proves this point.

One study mentions an indigenous Iranian tribe that still lived in the old ways. Eating practically no meat or dairy products these tribesmen still had perfect vitamin B12 levels, thanks to cross-contamination from the animals they lived with.

The bad modern days

The modern sanitization isn’t a problem unique to vegans.

Factory farmed animals (which is the majority being killed and eaten) are today being raised in such conditions that they actually need vitamin B12 supplementation. Else their meat would hold no B12!

But why go through the wasteful and barbaric process of supplementing B12 to our animal friends just so that we can eat them and thus get B12 ourselves? Why not go straight to the source?

Sources of vitamin B12

While Internet Rumours™ would have you believe there are no vegan sources of vitamin B12, there are actually a few. Not all are created equal though and there are pitfalls to look out for!

The biggest danger of sourcing B12 from vegan food is that the vitamin they contain is inactive – a pseudovitamin. This competes with active B12 for absorption, so it can actually speed up your deficiency.

Inactive pseudovitamin B12 can even be harmful for your nervous system.

The best way to be sure if a source is active is to measure urinary methylmalonic acid (MMA)after eating. Basically looking at how much B12 you pee out to determine how much was absorbed.

Following is a list of vegan B12 sources and their bioavailability.

Spirulina

Spirulina contains a bunch of vitamin B12 (35-38 μg per 100 g). Unfortunately it’s pseudovitamin and thus can’t be used as a source for your B12.

Chlorella

Chlorella contains a whopping 200-285 μg per 100 g and it’s been shown to be active!

Unfortunately it’s not entirely that cut and dried as other studies have failed to find any practical amount of B12 or have found that the vitamin is inactive.

Further, as a supplement the amount of B12 in chlorella tablet varies widely between producers. Some can be completely devoid of it.

It’s an interesting source but I wouldn’t rely on it.

Sea lettuce (ulva)

Sea lettuce is a group of edible green algae, including green nori. It contains a substantial amount of vitamin B12 at around 60 μg per 100 g of dried algae.

B12 in green algae is unfortunately a pseudovitamin .

Purple laver (porphyra)

The porphyra family of seaweeds is eaten all around the world. As nori in Japan, gim in Korea, and laverbread in Wales, for example. The porphyra family of seaweeds is eaten all around the world. As nori in Japan, gim in Korea, and laverbread in Wales, for example.

It has quite a bit of vitamin B12 and luckily it’s active !

Depending on where the seaweed is from, studies show that it contains anywhere from 30 μg to 130 μg vitamin B12 per 100 g of dried laver.

Seasoned and toasted products seem to cut the B12 content by half.

Vegan, Korean children do just fine with nori as their only source of B12 but that doesn’t seem to be the case for German vegans. From these studies, my guess is that 1) Korean nori contains more B12 and 2) Koreans by default eat a whole lot more nori than westerners.

Kimchi

Kimchi contains very, very little vitamin B12 (~0.02 μg per 100 g) and that might all be a derivate from the fermented fish sauce it’s made from.

Vegan kimchi (white kimchi) contains no B12.

Miso

Miso contains no active vitamin B12.

Tempeh

Soaking soybeans for the fermentation process of making tempeh increases its B12 contents substantially and so tempeh does contain a significant amount (0.7-0.8 µg per 100g).

However, it’s inactive B12.

Fermented black tea

This is a apparently a big thing in Japan and it’s not unusual to consume 1-2 liters per day of this brew.

While it does contain some active B12 (0.02-0.04 µg per 100 g), not even drinking these amounts is enough to cover your daily requirement.

Mushrooms

Black trumpet and golden chanterelle (personal favorite!) was found to contain 1.0-2.5 µg vitamin B12 per 100 g of dried weight. This can however vary a lot from farm to farm and is thus unreliable as a single source.

Commercially available shiitake mushrooms have been seen to contain even more B12 (~6 µg per 100 g of dried weight) but it too varied significantly between sources.

Asian food in general

A surprising amount of the plant-based B12 sources seems to come from Asian cuisine. This also happens to be a great source for a lot of vegan recipes! Mmm, bibimbap. 😋

Old, Korean women, for example, seems to be just fine B12-wise on a plant-based diet.

Sadly, few of us are lucky enough to eat locally sourced, homemade Korean food in a daily basis. It wouldn’t be wise to trust a western bastardization to yield the same results as a native Asian diet.

B12 deficiency

Many vegans are deficient in vitamin B12. The EPIC-Oxford study found that half of the vegans tested were deficient and expected to have a higher risk of developing clinical symptoms.

On average you lose 0.1-0.2% of your reserves per day (or 1.4 to 5.1 µg). If you don’t replace that you’ll eventually run out and risk some very serious health issues.

B12 deficiency can lead to anaemia, heart disease, dementia, psychiatric illness, suppressed immune system, bone marrow failure, and irreversible nerve damage.

Some typical symptoms include a loss of energy, numbness, tingling, blurred vision, sore tongue, reduce sensitivity to pain or pressure, confusion, poor memory, and hallucinations. There’s no sure-tell sign of deficiency. If you suspect a problem – go talk to a skilled medic.

Am I at risk?

Most vegans eat enough to avoid anemia and nerve damage but not enough to prevent heart disease or complications during pregnancy. It can have serious ramifications and should be taken seriously.

Two subgroups are especially at risk: those avoiding fortified foods (like raw foodists or macrobiotic vegans) and breastfed infants of vegan mothers who eat too little B12 themselves.

Infants are affected a lot harder by a deficiency than are adults. Diseases develop faster, are harsher, and more often result in permanent damage and retarded development.

How long does it take?

Your liver can store up to 2500 µg vitamin B12 and depending on how well your intestines can re-absorb lost B12 (enterohepatic circulation) it can take anywhere from a couple of years to a couple of decades before you become deficient.

How do I know?

The only way to know whether you’re deficient or not is to have a medical professional test you.

B12 level tests are notoriously variable however. Studies have shown that their results can vary 17-23% within the same individual. The most reliable is having a holotranscobalamin test.

If you’re low on B12 (and remember, lots of vegans are) you need to start supplementing.

Rate of absorption

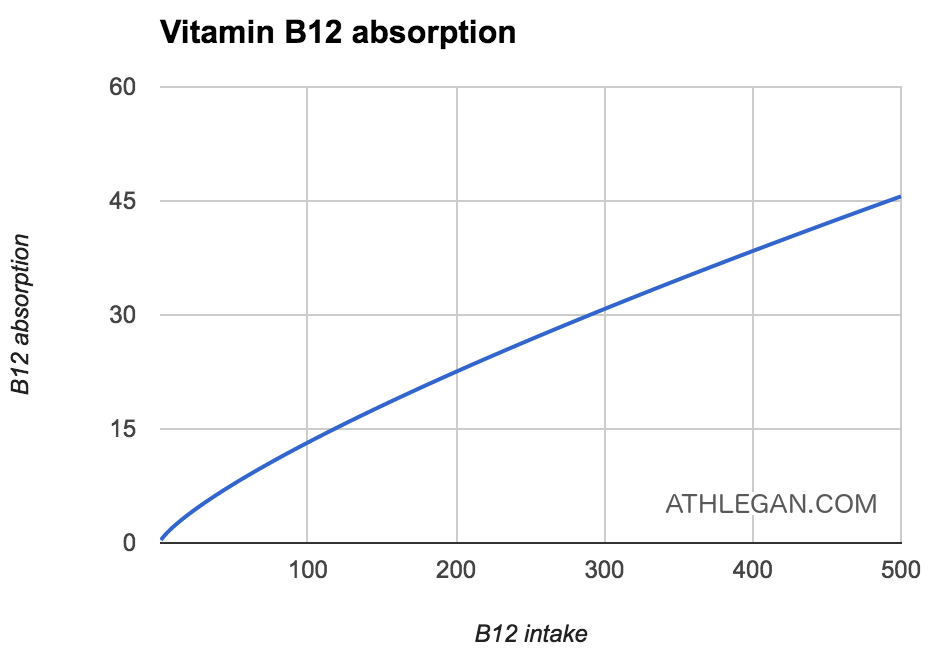

Not all consumed B12 will be absorbed. In fact, the higher the dose the less efficient your absorption.

One systematic review came up with the following equation for how much we absorb:

LN(Absorption) = 0.7694 * LN(Intake) - 0.9614

If we plot that to a graph it’ll look like this:

You absorb almost 2 µg from taking 8 µg but only just over 3 µg from taking 16 µg. It’s almost linear but doesn’t scale 1:1, so you’ll have to take more than double to be able to absorb double. You absorb almost 2 µg from taking 8 µg but only just over 3 µg from taking 16 µg. It’s almost linear but doesn’t scale 1:1, so you’ll have to take more than double to be able to absorb double.

The absorption also depends on the type of cobalamin you’re eating. Protein-bound B12 is, for example, less well absorbed than crystalline B12 (cyanocobalamin) .

Further, if you take the B12 just after eating it’ll absorb only half as well.

Those are the biggest variables for determining how much you absorb but there are more. Drinking alcohol, consuming huge quantities of vitamin C, calcium deficiency, pancreatitis, tapeworms, consuming pseudovitamin B12, etc. Lots of things that can screw with your absorption.

Smoking was thought to disturb the metabolism of vitamin B12 but when tested this doesn’t seem to be the case. There are other reasons you’d want to stay away from smoking though. 😉

Vitamin B12 supplementation

You could use fortified foods like vegan milk or breakfast cereals to get your B12. Because they don’t contain a whole lot, however, and since absorption decreases with higher doses, you’d have to consume it several times per day.

That’d work – drink a big glass of fortified milk with each meal and snack and you should be good.

Personally I’m too undisciplined to make that work and instead I opt for B12 supplement pills.

We want to make up for the 1.4-5.1 µg lost per day and just to be sure we’ll place ourselves in the far end and aim for 5 µg. Based on the above, we can run the numbers and come up with an estimate.

Here’s my recommendation: take 50 µg per day OR 500 µg per week.

I’m not only undisciplined but also very forgetful (yeah, I’m quite the catch) and so I try to pop a 500 µg pill every few days, which results in just a little more than twice per week. This strategy also helps me refill my levels after traveling every now and then and forgetting the supplements at home.

Go with cyanocobalamin – it’s the cheapest and works just as well as other, more expensive forms of B12 – and take the supplement on an empty stomach to optimize absorption.

Don’t listen to recommendations to inject B12, as it likely comes from ignorance of recent medical studies. Oral supplementation is just as a effective and modern medical science recommends that form .

Standard recommendations

Dr Michael Greger (of How Not to Die and Nutrition Facts fame) recommends the following:

- At least 2,500 mcg (µg) cyanocobalamin once each week, ideally as a chewable, sublingual, or liquid supplement taken on an empty stomach

- or at least 250 mcg daily of supplemental cyanocobalamin (you needn’t worry about taking too much)

- or servings of B12-fortified foods three times a day, each containing at least 25% U.S. “Daily Value” on its label

- Those over 65 years of age should take at least 1,000 mcg (µg) cyanocobalamin every day.

Other medical professionals recommend the following:

- Eat fortified foods two or three times a day to get at least three micrograms (mcg or µg) of B12 a day

- or take one B12 supplement daily providing at least 10 micrograms

- or take a weekly B12 supplement providing at least 2000 micrograms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which form of B12 should I take?

The most common ones are cyanocobalamin, methylcobalamin, and hydroxycobalamin.

There’s little money to be made from selling a cheap bulk product. Just like with creatinemarketers have therefor come up with alternatives that are hailed as so much better than the base product.

Don’t waste your money – go with cyanocobalamin. With some caveats!

- If you have trouble metabolising cobalamin – go with hydroxocobalamin instead.

- If you suffer from kidney failure, are a smoker, or practically base your diet on cassava – go with methylcobalamin instead.

What happens if I take too much B12?

There’s no established upper limit for vitamin B12. Very high doses have even shown to be very beneficial for professional marksmen.

Does this mean veganism isn’t viable?

B12 supplementation is the last carnist defense after fearmongering vegan protein deficiency.

The argument is that adding B12 to our diet makes it non-viable. But guess what?

The argument is that our vegan diet is non-viable because we have to add B12 supplement to it. But guess what? So does meat eaters! Only the farmers do it for them, just like fortified foods producers do for vegans.

Further, protein-bound B12 is much harder for our bodies to absorb and this gets worse with age.

In summary

Vitamin B12 deficiency is a real threat, especially for vegans. The ramifications can be severe and we should take precautions not to run the risk of becoming deficient.

Luckily, it’s very easy to avoid.

Pop a cheap 500 µg cyanocobalamin pill once per week or 50 µg once per day and you’re good.

Footnotes:

- Plasma vitamin B-12 concentrations relate to intake source in the Framingham Offspring study.

- Sensitivity of serum methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine determinations for diagnosing cobalamin and folate deficiencies.

- Cobalt: Its Role in Health and Disease

- Vitamin B-12: plant sources, requirements, and assay.

- Neurologic abnormalities in cobalamin deficiency are associated with higher cobalamin “analogue” values than are hematologic abnormalities.

- Metabolic vitamin B12 status on a mostly raw vegan diet with follow-up using tablets, nutritional yeast, or probiotic supplements.

- Vitamin B12 and seaweed.

- Purification, identification, and characterization of methylcobalamin from Spirulina platensis.

- Pseudovitamin B(12) is the predominant cobamide of an algal health food, spirulina tablets.

- Characterization and bioavailability of vitamin B12-compounds from edible algae.

- Purification and characterization of a corrinoid compound from Chlorella tablets as an algal health food.

- Deficiency of vitamin B12 in Chlorella.

- Purification and characterization of corrinoid-compounds from the dried powder of an edible cyanobacterium, Nostoc commune (Ishikurage).

- Characterization of a vitamin B12 compound in the edible purple laver, Porphyra yezoensis.

- Vitamin B12-Containing Plant Food Sources for Vegetarians

- Purification and characterization of a corrinoid-compound in an edible cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon flos-aquae as a nutritional supplementary food.

- Characterization of vitamin B12 compounds from Korean purple laver (Porphyra sp.) products.

- Serum vitamin B12 levels in young vegans who eat brown rice.

- The influence of a whole food vegan diet with Nori algae and wild mushrooms on selected blood parameters.

- Vitamin B12 Contents in Some Korean Fermented Foods and Edible Seaweeds.

- Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability.

- Formation of B-vitamins by bacteria during the soaking process of soybeans for tempe fermentation

- Characterization of vitamin B₁₂compounds in the wild edible mushrooms black trumpet (Craterellus cornucopioides) and golden chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius).

- Vitamin B12 is the active corrinoid produced in cultivated white button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus).

- Dietary source of vitamin B12 intake and vitamin B12 status in female elderly Koreans aged 85 and older living in rural area.

- Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate in British male omnivores, vegetarians and vegans: results from a cross-sectional analysis of the EPIC-Oxford cohort study.

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline.

- Systematic review on daily vitamin B12 losses and bioavailability for deriving recommendations on vitamin B12 intake with the factorial approach.

- How I treat cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency

- Mechanism of enterohepatic circulation of vitamin B12: movement of vitamin B12 from bile R-binder to intrinsic factor due to the action of pancreatic trypsin.

- Cobalamin-responsive disorders in the ambulatory care setting: unreliability of cobalamin, methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine testing.

- Diagnostic accuracy of holotranscobalamin, methylmalonic acid, serum cobalamin, and other indicators of tissue vitamin B₁₂ status in the elderly.

- Atypical cobalamin deficiency. Subtle biochemical evidence of deficiency is commonly demonstrable in patients without megaloblastic anemia and is often associated with protein-bound cobalamin malabsorption.

- Food cobalamin malabsorption occurs frequently in patients with unexplained low serum cobalamin levels.

- Incidence and clinical significance of protein-bound vitamin B12 malabsorption.

- Oral treatment of pernicious anemia with high doses of vitamin B12 without intrinsic factor.

- Cobalamin coenzyme forms are not likely to be superior to cyano- and hydroxyl-cobalamin in prevention or treatment of cobalamin deficiency

- Oral cobalamin remains medicine’s best kept secret.

- Oral cobalamin (vitamin B(12)) treatment. An update.

- Comparing the efficacy and tolerability of a new daily oral vitamin B12 formulation and intermittent intramuscular vitamin B12 in normalizing low cobalamin levels: a randomized, open-label, parallel-group study.

- Efficacy of oral cobalamin (vitamin B12) therapy.

- Cobalamin deficiency in the elderly: aetiology and management: a study of 125 patients in a geriatric hospital.

- Methionine auxotrophy in inborn errors of cobalamin metabolism.

- Cobalamin metabolism and its clinical aspects.

- Improvement of fine motoric movement control by elevated dosages of vitamin B1, B6, and B12 in target shooting.

|