“It’s Just An Animal”: How Language Takes Away Personhood

By Hanh Nguyen

“The following chapter is excerpted from Tongue-Tied: Breaking the Language Barrier to Animal Liberation by Hanh Nguyen (copyright 2019). It is reproduced with permission of Lantern Publishing & Media.”

MOST AMERICANS LEARNED IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL THAT A NOUN is a person, place, or thing. MOST AMERICANS LEARNED IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL THAT A NOUN is a person, place, or thing.

Where do other animals fit in, then?

They are not places. And lest one is tempted to put them in the “person” category, which of course means only human persons, one is reminded that to do so would fundamentally contradict humans’ self-aggrandizing view of our own species. So other animals remain a forgotten category; in reality, though they are not things in the same way the computer I’m using to type this sentence is a thing, most of them are treated not much better than inanimate objects. According to grammar guides, they are “somethings.” We ought to say “The fox that jumps over the fence,” not “who.” After all, they are “just animals.” In the world of law, many of the most vulnerable other-than-human animals aren’t even “animals” at all: the U.S. Animal Welfare Act, the only federal law regulating the treatment of animals in experimentation, exhibition, transport, and by dealers, uses an absurd definition of “animals” that excludes birds, rats and mice bred for vivisection, horses not used for “research purposes,” and a broad category of “other farm animals.”

An exclusionary definition of personhood is foundational to Western philosophy. The last chapter already hinted at this aspect of the Aristotelian view of philosophical and political personhood: Aristotle placed so much emphasis on political participation in the determination of who is considered a citizen—a full-fledged member of human society—that he didn’t even put all humans on equal footing. Those who lacked the cognitive capacity to participate in deliberative or judicial office, according to his judgment, were fit only to serve as natural slaves.

As a result, in Western thought, personhood and the moral consideration to which a person is entitled as sociopolitical constructs have traditionally been inextricably linked to related notions of free will or personal power, equality, liberty, and rights. Even though Aristotle’s views on slavery would horrify most people today, the worldview that defines modern Western society is one in which the patriarchal Man (capital “M”) wields the power to overcome nature and his proverbial inner “beast” at every turn to transcend the realm of mundane life in pursuit of happiness and spiritual enlightenment.

However much the idea of personhood might be proclaimed by philosophers to be universal, natural, or “God-given,” in practice it’s anything but. Time and again, personhood has served as a political tool to grant rights or revoke them at will, to reinforce the boundaries of civilization and exclude entire groups, human and otherwise.

In practice, those considered “subhuman” or “quasi-animal” beings have always conveniently occupied the buffer zone between civilized Man and the “brutes.” Comparisons to animals or animal bodies undermine personhood so effectively because other-than-human animals can claim none to begin with.

In ancient China, peoples other than the Han Chinese were said to have characters that made them closer to animals. In fact, the word Ti (referring to northern barbarians) was written with the Chinese radical (a graphical component of a character) meaning “dog,” while the word Man (referring to southern barbarians) was written with the radical meaning “worm.”

Anti-Semitic propaganda disseminated under the Nazi regime in order to instill fear and disgust among the population frequently compared Jews to lice or rats who carried disease, flooded the continent, and devoured precious resources.

Leading up to the Rwandan genocide, which destroyed 800,000 members of the Tutsi ethnic group, radio messages and propaganda called Tutsis “cockroaches” who needed to be exterminated for the country to prosper.

In 2018, we seem as far as ever from a “post-racial America” as newspapers report on police officers calling black Americans, whether they are adults or just children, “wild animals” to be “put down.”1 Animalization has come to mean the same as the worst form of degradation—dehumanization.

Similarly, in Vietnamese, the word súc sinh is such an insult to one’s dignity and humanity that it could form the basis of a lawsuit. Súc in Sino-Vietnamese means “to raise,” while sinh refers to a living being. Súc sinh, which shares the same root as súc vt and gia súc (gia meaning “house” or “residence”), translates to “cattle” or “livestock”—species of animals raised for their flesh or for their labor who are thought to be by nature unintelligent and unclean, the most despised of all animals. By the same token, those deemed “barbarians” or “savages” are said to exhibit behaviors close to those of “wild” animals; they are often described by the words thú tính or dã tính. Thú here is the equivalent of “beast,” while dã means “wild,” and tính translates to “characteristics.”

Today, most English speakers still refer to most other-than-human animals by the same pronoun used to refer to a table—“it”—whereas many beloved vehicles, mechanical objects, even musical instruments are metaphorically gendered as “she” (they are seldom “he,” this asymmetry often being attributed to the historical objectification of women), and these material possessions are given infinitely better care and more respect. An exception to this established custom is clarified in both the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA style) and The Associated Press Stylebook (AP style), which rule that an other-than-human animal with a name may be referred to using gendered pronouns. Only when the relationship is personal is it acceptable to use “he” or “she” when referring to that individual. A news article about a dog named Skippy may actually use “it” to refer conceptually to all dogs and specifically to Skippy before his name is mentioned—from then on, the pronoun “he” may be used.

There is hardly any species whose members are always either “he” and “she” or “it.” Pronoun use tracks interpersonal relationships more so than species boundaries. That is, “s/he” pronouns are only extended to some of those who come into close contact with humans: other-than-human animals earn their gendered pronouns—and, by extension, their gendered identity—only through their association with humans.

Individual names are even rarer, largely restricted to those whom we really like and keep in our homes, who may be allowed to have an identity the way we do. Even then, the legitimacy of these names may not be fully recognized, and may even be diminished: some news articles still encase other-than-human subjects’ given names in scare quotes, especially in the case of names that sound a little too “human.” By contrast, a “stray” dog, a free-living wolf, and a pig farmed for their flesh are not important enough to us that we have names for them, so they all share the same objectifying pronoun. Now, it’s interesting to note that many adult humans would also refer to infants as “it”; they are not proper subjects in the sense that they have not fully developed a personality or self-awareness. Human infants nonetheless still obviously enjoy the benefits of being human, as their perceived lack of personhood doesn’t justify caging, beating, or otherwise mistreating them.

This is, in all likelihood, not a coincidence. Before 1847, when a case brought to the New York State Supreme Court on behalf of Mary Ellen, an abused ten-year-old girl, won a legal milestone for children’s rights, children were in a very concrete sense the property of their parents, who could treat them however they deemed fit. A popular, if apocryphal, account of the court proceedings quotes Henry Bergh, founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), who took it upon himself to help the child. Bergh reportedly said: “The child is an animal. If there is no justice for it as a human being, it shall at least have the rights of the cur in the street. It shall not be abused.”2 The statement may be fictional, but the sentiment is not.

Although there have been many victories for children’s rights since then, children are in the same situation as other-than-human animals in that they are considered inferior beings and vulnerable members of society; their rights are recognized on a discretionary basis, if at all. Modern child-trafficking and the selling of children into slavery or forced marriage, sometimes by their own parents, begs the difficult question of whether we have truly progressed past our view of young humans as property, as “somethings” rather than “someones.”

Similar human-centric distinctions in pronoun use exist in Vietnamese. A notable characteristic of the Vietnamese language is its intricate system of pronouns, which plays an important role in “deference rituals” and in maintaining a strict social order.3 The pronouns used vary depending on one’s age, attitude, and the level of respect demonstrated toward the person being addressed. Within this system, distinct third-person pronouns are used to express respect for people who are older or those who belong to a social class at least equal to one’s own, such as anh (referring to an older man), ch (referring to an older woman), or the plural h.

By contrast, nó (singular) or chúng and chúng nó (plural) are third-person pronouns that one may use when “talking down” or that imply the lower rank of the person being referred to. These pronouns are used for other-than-human animals, children, or lower classes of adults, including criminals, low-lifes, or villains in a story. Although the Vietnamese pronoun system does not completely reduce other animals to the status of inanimate objects in the way that the English “it” does tacitly, there is a palpable degree of condescension. Tellingly, con as a noun means “child” or “small thing”; as a classifier, it indicates other-than-human animals and various classes of objects; and it also functions as the pronoun used in conversation with one’s child or a person much younger than oneself, the generic pronoun for other-than-human subjects, and an infantilizing, if not outright condescending, pronoun for women. On the rare occasion a human addresses an other-than-human person directly—speaking to instead of about them, the pronouns used are often tao (offensive “I”) and mày (offensive “you”), which often convey a derogatory undertone or else indicate extremely informal language used only between close friends.

Although the exact form that it takes varies between languages (for example, in French, a gendered language, every noun, including inanimate objects and other-than-human animal species, is either masculine or feminine, and pronouns follow this classification), the use of pronouns with regards to other-than-human referents is in many ways symbolic of our glaring failure to recognize other animals as individuals.

Even so, there is no dearth of evidence of this attitude elsewhere in our vernacular. Take for instance the plural of “fish,” which is still “fish.” I believe it is no coincidence that many of the nouns with invariant plurals denote other-than-human animals—“deer,” “elk,” “antelope,” “sheep,” “fish,” “cattle,” “swine”; these are often species who have historically been either herded or hunted, especially for their flesh, as a theory in linguistics suggests (though it remains unproven). It has been suggested that the fact that “herd” animals are often grouped together as homogenous masses and the custom of referring to hunted animals in the singular (“We hunt bear, otter, beaver, deer, rabbit, raccoon, turkey . . .”) may very well have helped inhibit plural regularization during the evolution of the English language.4 Indeed, some of these nouns may have started out as singulars of mass. For instance, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe observes: “I frequently caught Fish enough, as much as I car’d to eat.” As a general rule and for the remainder of this book, I pluralize uninflected plural nouns that are species names in the regular way, by adding –s or –es, to emphasize the personhood of each referent.

If the personhood of other-than-human mammals is already overlooked, the question of fishes’ personhood must seem ludicrous to most of us. One need only look at how thoroughly fishing and industrial “aquaculture” have abused the ocean and the beings who call it home, or how their catch counts don’t even attempt to provide an enumeration of the individuals caught, measuring them only by weight, in tons. And imagine, if you will, a mirror universe in which your biological classification stood in as a verb for another species’ torture, mutilation, and murder of you and those of your kind, all in the name of a sport or a wholesome “outdoor” “father-and-son” activity. Isn’t that precisely what “fishing” is? When they are quite literally “fished out” of their home, fishes have not merely been caught—they become “catch.”

Indeed, except for the few animals whom we share our lives with, we humans think of most other animals as faceless masses, exemplified by the environmental protection movement’s mission to protect “endangered species,” even when individual members of that species are not themselves under immediate threat. It is also not the case that we distribute our concern for all endangered species evenly. The species that garner the most attention and appear most often on conservation organizations’ posters are invariably those who have aesthetic value to us—so-called charismatic megafauna, such as polar bears, white rhinoceroses, pandas, and whales. It is largely the loss of aesthetic value implied by these species’ extinction that we lament, not so much the fact that their disappearance may cause real suffering for other beings in the same ecosystem.

The language used to refer to free-living other-than-human animals makes it especially clear that we deal in “populations” and “species,” catch-all terms and abstractions, of which individuals are merely lifeless “samples,” “specimens,” or “units.” There are no interpersonal relationships between these identical units. The individual is already metaphorically dead, subsumed into the collective noun. One may receive a hefty fine for illegally poaching or trading an endangered species (that is to say, an individual or individuals belonging to said species), but the death of a “common” deer is no tragedy—indeed, it may even be construed as beneficial “population control.”

At the other extreme, “invasive species” need to be mercilessly “culled.” In December 2018, Congress passed a bill to allow sea lions in the Pacific Northwest to be persecuted for eating salmons to live, in order to protect the latter. (Curiously, no matter how much destruction we bring upon other animals and their homes, we humans never fall under this definition of “invasive,” and our intrusiveness is instead branded as the price of progress.) Despite these radically different reactions and rationalizations, the price paid by each individual target of human violence is equally tragic.

Similarly, the other-than-human animals whom we purposely breed in order to exploit are so dispensable that for corporations they are reduced to ear-tag numbers; for consumers they are represented by product codes. Like all animal species subject to “selective breeding,” “Thoroughbred” horses who are bred to be raced when they are mere teenagers are never their own persons existing in the now; of utmost importance is the purity of their blood—their membership of a lineage extending far into the past and the future. If they are genetic successes, they in turn become breeding “stock.”

At the most fundamental level, we bundle together all other-than-human species and speak in the most generic terms of “animals,” which twentieth-century French philosopher Jacques Derrida denounces as a violent gesture in itself: to do so is already to enclose “the animal” in a cage and flatten radical differences; it is a conceptual simplification with very real, violent consequences. Not only do we act as if humans don’t fall under that classification (we habitually say “animals and humans” or “animals or humans”), but the very word “animal” by default carries with it connotations of inferiority. That we see other animals more as a type than as individualized identities is further exemplified by the idiom “a different animal,” in which the generic naming of “animal” extends beyond the biological definition.

Even for animal advocates, being reminded daily of the enormity of the atrocities we are working to end means we may temporarily forget to look away from the statistics once in a while, even as we ask others to adopt a vegan lifestyle to spare up to two hundred lives per year—of whom X are cows and Y chickens and Z fishes. In my own research, I often have to stop and remind myself that each footnote, each entry in a database I come across, correlates with an individual with a face and a story.

When you deliberately look past another’s personhood, you only see them as a means to an end, as nothing more than an instrument. Some of the historical events that for us represent the most grievous affront to human rights demonstrate this principle. For instance, Korean girls and women who were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II were called “comfort women.”

Other animals’ statuses in a world that has come to be dominated by humans are similarly decided by names that recognize them only for their designated function and coerced labor.

“Farm animals” and even the proposed alternative, “farmed animals,” used by many animal advocates, obscure the ruthlessness of a system that operates under the guise of the benign concept of “agriculture,” instead aligning its victims’ forced participation with their identities or their lives’ purposes; the inside of the “farm” is likely the only reality they will ever experience. “Pets” is, by definition, only a slight improvement upon “plaything,” referring to other-than-human beings “tamed” and kept for pleasure. Likewise, “service animals” or “emotional support animals” and even “companion animals” identify beings by their potential benefit to humans. Although profound bonds are certainly forged between many humans and their “service” or “companion” animals, we as a society care only that these nonhuman others provide their companionship as a service to humans, and as such may fly with their caretakers under an airplane seat instead of as cargo. Other common examples, such as “hunting dogs” and “dairy cows,” also come to mind.

Many of the other-than-human animals exploited by humans come to be defined by the place that confines them and the system that enslaves them; for example, “laboratory rats.” The place of imprisonment sometimes stands in as the subject of a sentence to imply all of the individuals trapped inside that structure, as if they were the equivalent of machinery attached to the building (“Pullet barn likely a totally loss from fire”). Syntactically, the term “farm animals” is not different from “sea animals” or “land animals”—that these individuals “live on” the site of their exploitation almost seems like a matter of biological necessity. Likewise, we have adopted the industry term “zoo habitats,” which makes glorified cages and prison cells seem homely, a perfectly adequate if not superior substitute for the natural homes of the zoo’s “residents.” In Vietnamese, the word for “rat” literally translates to “sewer mouse” (chut cng), perpetuating stereotypes about the species as unclean and disease-bearing beings.

In the same way their personhood is reduced to their function, other animals are seldom more than the sum of their parts. The human gaze is invariably a violent one, slicing other animals into “breast,” “thigh,” and “drumstick”; “loin,” “ham,” and “shank”—even while they’re still alive. Other-than-human animals’ flesh isn’t just labeled by parts, but also by biochemical makeup as “animal protein” or particular types of “fats”; their flesh is broken down into cellular components so that it may be replicated or reproduced as an infinite resource. Diverse groups of sea-dwelling animals are rendered edible through their classification as “seafood” (the French go so far as to call them fruits de mer, literally “fruits of the sea”); their flesh, however, is not “meat.”

After all, exploited other-than-human animals are not perceived as separate from the various “products” that can come from their bodies. Many humans are able to look at a “cute” picture of a chicken, or maybe even a real-life pig standing in front of them, and still utter words such as “tasty” or “breakfast” in reference to that other-than-human individual.

The process whereby the living being is reduced to lifeless cooked flesh is thoroughly truncated. Because they’re not human, their once-moving body, now a lifeless “carcass” (which in itself is less dignified than a human “corpse”), magically becomes various cuts, or altogether undifferentiated “meat.” Pigs become “pork,” cows become “beef,” and chickens become, well, “chicken.” In the last example, the noun may stay the same, but “the chicken” on the plate no longer has any connection to “the chicken” whose life was extinguished for that meal.

We have “grass-fed beef” and “grass-fed dairy,” but the cow who presumably eats the grass is out of the picture altogether. We have precisely measured and packaged Quarter Pounders. A chicken’s wings, stripped of most of their functionality through domestication, become “chicken wings,” which no longer carries any sign that a being once possessed or still possesses those body parts. The same principle applies to “mink fur,” “goose down,” “pig heart,” and “cowhide” (which has amazingly even become one word!). In fact, the species names in these instances are functionally equivalent to adjectives. The other-than-human being as a subject no longer appears in the marketing of their body parts. An apparent exception to this observation, the term “cow’s milk” keeps the possessive indicator, but now all cows exploited for their milk have been reduced to one generic being.

The “meat” and “leather” that we hack off other animals’ bodies are made of the exact same stuff as our own skin and flesh. Likewise, there is little by way of real chemical distinction between “hair” and “fur,” and yet to admit that this bifurcation separating hominids (some of the great apes such as humans, chimpanzees, and orangutans, and our fossil ancestors) and other animals is false would bring us dangerously close to the “lower beasts.” Our lexicon reflects our diligence in enforcing these boundaries between human and other animal.

In Vietnamese, however, this linguistic dissonance is less pronounced. The word for “meat” () is the same for both human and other-than-human animal flesh. “Pork” translates quite literally to a compound word consisting of “flesh” and “pig” (); the same is true of chickens’, cows’, or any other animal’s flesh. The names of many though not all body parts, such as “skin” (da), “fur” or “feathers” (lông), and organs such as “heart” (tim) or “liver” (gan), remain unchanged after the death of an other-than-human being. Again, these names apply to both humans or other animals, and perhaps most tellingly, there is an enduring belief in Vietnam that eating a given organ directly benefits the analogous organ in one’s body, possibly due to the assumption of similar biochemical makeup. These divergences from the anglophone world do not mean that the belief in human superiority does not exist in Vietnamese culture, merely that it is rationalized and interacts with the language system differently.

Surprisingly enough, dogs’ meat has historically gone by several names in Vietnamese, not all of which follow a plain and self-explanatory format, including mc tn—the two syllables are Sino-Vietnamese characters representing a play on a Vietnamese word for “dog.” According to renowned historian Trn Quc Vng, the practice of eating dogs has its origins in traditional sacrificial rites; initially, only spirit priests and sorcerers consumed the sacrificed dog, and they did so only in private out of guilt. Euphemisms for “dogs’ meat” emerged because of this cultural guilt, which predates the arrival of Western influence, a fact that may surprise many in the West.

Even when we do agree on which other-than-human animals to eat, we put different price tags on different body parts according to arbitrary, culturally determined taste preferences and (often misguided) beliefs about health. That Americans overwhelmingly prefer and are willing to pay a markup for white meat (chickens’ breasts) still boggles my mind, as I recall many a family meal of my childhood in which I would be given the chicken’s thigh, made up of darker meat, which was and still is considered the best part of the chicken’s body. These market differences work extremely well with regards to the economic problem of surplus chickens’ legs in the United States. We are no longer dealing with the dismembered bodies of chickens selectively bred to be obese and whose legs are atrophied from confinement by the time they are butchered, but merely minimizing the wastage that is a necessary part of production.

As raw materials, parts of the living other-than-human individual that might negatively affect productivity or even incur extraneous expense are systematically and methodically done away with. The mutilation of various body parts, which occurs mere days or weeks after the individual’s birth, is reproduced syntactically through the plain language of “debeaking” and “dehorning.”

Other animals’ species and their species-specific features also become their defining, if not only, characteristic. We rarely refer to other-than-human animals by nouns other than their species name. By contrast, it would be quite odd if we only referred to each other as this, that, or somebody else’s “human.” Instead, we recognize each fellow member of our species as a unique “person,” an “individual” whose experience isn’t reduced to their humanness; because the point of reference for personhood is by default human, no qualifier to these terms is needed. We make use of relational nouns to introduce our partners, our friends, and our relatives, but often don’t realize that other animals, including those we see only as “products,” are also mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, friends, peers, and leaders in their communities. All of them bring a “unified psychological presence,” as the late philosopher Tom Regan puts it, to the world.5 Language that is too literal a reminder of this reality can thus bring great discomfort. I recently stumbled across a photo online that showed a dead chicken’s foot placed on top of an egg. Captioned “A mother’s touch,” the image elicited not a few comments on its dark nature. And even though a great number of other-than-human individuals are lifelong companions and best friends of humans, “my (dog or canine) companion” instead of just “my dog” would surely raise an eyebrow or two.

This paucity of relational words in reference to other-than-human animals oversimplifies their relationships—with humans as well as each other—and obscures categories beyond the level of species that encompass all of us and the shared experiences that connect us as animal kin.

But even more uncustomary is recognizing other-than-human individuals as proper victims. We dismiss the majority of them as merely “dumb beasts” (“dumb” being the Old English word for “mute, speechless”) who have no concept of existence beyond immediate sensations of pain and pleasure, no moral compass, and thus no rightful claim to fair treatment.

They are not victims; they are neither enslaved nor murdered. Instead, they are “bred,” “reared,” then “slaughtered”—usually “humanely,” of course, which makes us feel significantly better about the whole sorry affair. Worse, the euphemistic language developed by the same industries that physically morph living beings into profit-generating machines discursively turns the act of killing into “processing” or “harvesting.”

No atrocity or massacre is ever committed against other-than-human animals. Most important, although trillions of other-than-human beings perish at the hands of humans every year, they have no entitlement to justice; in both word and deed, humans erase their suffering. Under an online news article about a fire that took the lives of more than 100,000 chickens at an industrial egg farm in 2016, a reader half-jokingly asked if there would be a barbecued chicken sale in the next few days to take advantage of the situation.6 A news article covering a similar tragedy that left about 1,200 pigs dead notes that “no one was hurt in the blaze that caused more than $1M in damages.”7

I once got into a heated argument with my mother over this exact issue—the use of the Vietnamese word for “victim” to refer to other-than-human individuals exploited by humans. The difficulty of my situation was compounded by the fact that the Vietnamese word itself (nn nhân) by definition excludes other-than-human subjects. Nn nhân is made up of two SinoVietnamese characters, one of which means “person,” which is always understood to be human. The same character makes up the words cá nhân (“individual”), nhân cách (“humanity”), and nhân đo (“humane,” which is understood in the same context as in English). In the same vein, ngi in Vietnamese translates to both “human” (the species name) and “person.”

As most humans have not expanded their moral circles to include nonhuman others, it’s understandable that victimhood is still largely reserved as a human privilege. By questioning other animals’ qualifications for victimhood, we relieve ourselves of the obligation to consider the ethics of our actions. The oft-cited reasons for which other-than-human animals are denied consideration as victims—that “they don’t feel pain as humans do,” that “they can’t possibly know they are being mistreated”—sound all too familiar. If the general principle were true, that supposed reduced sensitivity to pain or inferior cognition rendered rights violations acceptable because of the victim’s inability to recognize these as violations, why stop at other-than-human animals? We used to justify the atrocities humans committed against each other by reasoning that certain groups were less intelligent and less susceptible to pain by virtue of their physiognomy, skin color, or ways of life—views that were all supposedly backed by scientific consensus.

Indeed, the low social standing we force upon other animals often is attributed to intelligence—or, in this case, a presumed lack thereof. As we consider ourselves the apex of evolution, we declare human intelligence the model for all living creatures to emulate. By this narrowly defined criterion, only a handful of species are smart enough to warrant our protection.

As far as most of us are concerned, a “likeness-to-human” meter continues to determine “evolvedness” and whether an other-than-human species merits consideration, again usually only to not be grossly mistreated. This standard is dubious at best, coming from a species that hasn’t been able to agree upon a universal definition of intelligence for itself and has yet to learn to treat members of its own kind with perceived impaired cognitive function with universal respect. Intelligence, in itself a value-neutral aspect of a being’s psyche, has throughout history upheld oppressive ideologies and, in turn, oppressive policies in areas such as housing, education, employment, and health care.

In the early 1900s, scientists were using the newly established IQ test to sort people with mental disabilities into different grades of deficiency based on their respective “scientifically quantified” mental age. These individuals, who were forced to bear such scientifically precise labels as “imbeciles,” “idiots,” and “morons,” were also said to display “animal propensities” and “primitive savagery.” Intelligence also figured prominently in the determination of racial demarcations.8 In the early twentieth century, various immigrant populations from southern and eastern Europe, including Russians, Poles, Italians, and Jews, were called different “races,” even though now they would all be categorized as Caucasian or white. They were considered to possess unstable personalities and inferior intelligence, which made them more suited to backbreaking manual labor and which threatened the advancement of American society as a whole.

By the end of the century, the category of whiteness had been extended to include the descendants of those who migrated from Europe decades earlier. However, the 1994 publication of the book The Bell Curve, which sought to prove the existence of a persistent black–white IQ gap, made it clear that a racialized view of intelligence remained as popular as ever and that we were far from overcoming our obsession with quantifying intelligence using only the socially dominant, Western conception of the term.

We now know that standardized tests of intelligence, including the IQ test, have failed miserably at capturing diversity in cognitive abilities among populations. They have proven to be plagued with cultural bias, are highly dependent on factors such as social, cultural, and economic contexts, and are not necessarily indicative of biological discrepancies. If anything, they perfectly illustrate disparities in education or employment opportunities and other measures of social inclusion. Just as modern scientific discoveries, notably the famous Human Genome Project, have shown that there is vastly more variation within a single population than across different populations of humans, thus discrediting the pseudo-scientific backing for arbitrary biological categories of race, scientists continue to uncover qualities and capabilities possessed by other animals that were previously thought to be exclusively human, a result that should have become apparent to all those who came after Darwin.

Studies published between 2015 and 2017 as part of the Someone Project showed that chickens and pigs have complex social lives and demonstrate empathy toward their peers; they also boast an understanding of numerical quantities and a symbolic language (one devised by humans, of course, as all animals speak their own languages).9,10 And if there is still any doubt that other animals are capable of moral reasoning, studies at the University of Chicago have shown that rats will forego a chocolate treat to save companions in distress—say, being trapped in a pool of water, which made the latter very uncomfortable even if they weren’t at risk of drowning—especially if the rats facing the moral dilemma have had similar unpleasant experiences themselves.11

As it turns out, how cognitively complex someone is has nothing to do with how much they resemble us or how fond we are of them. In fact, according to Animal Behavior, other-than-human animals who are cleverer according to our own litmus test have a higher chance of butting heads with and outsmarting us, thus becoming “nuisances” in our lives. Think of crows who make use of their excellent memory to steal food from us, elephants who figure out how to unplug the power source of an electric fence, and raccoons who quickly learn how to open specialized trash containers. Yet we label the same amazing individuals “pests.”

These flimsy foundations upon which speciesism is built, no matter under what name—intelligence, reason, or rationality—all crumble upon close examination. We begin to realize how little we know about other animals yet how often we disregard them based on pure ignorance or otherwise biased assumptions.

One of the most arrogant proclamations that we humans have made about ourselves is that only our species is capable of language. We’re always trying to teach this supposedly one-of-a-kind communication system to other animals. The late Koko the gorilla could comprehend two thousand words of spoken English, using a modified form of American Sign Language to express happiness, sadness, love, grief, and embarrassment. Alex the African grey parrot could say 150 English words and combine words to create new meanings; his last words to his human guardian reportedly were, “You be good; see you tomorrow; I love you.” Bruno the chimpanzee, who was also competent in American Sign Language, used the very language of his captors to express KEY and CUT, demanding his freedom from the laboratory cage.12

Yet we have seldom taken the time to decode an octopus’s color-shifting display or a whale’s song. At the very least, the very canine companions with whom we share our homes for a decade or longer diligently learn many words in our vernacular, yet we seldom return the gesture.

Intelligence, especially when commonly and broadly understood to mean any sort of deliberate mental work as opposed to instinct, varies not only in degree but also in kind and dimension. Within our own species, we can identify social, emotional, logical, musical, spatial, and many other types of intelligence. Measuring other animals’ intelligence against our own, which is what we’ve always done, gives a skewed and at best incomplete view of their inner worlds, the full complexity of which humans may never grasp. Mark Twain once said: “It is just like man’s vanity and impertinence to call an animal dumb because it is dumb to his dull perceptions.”

The mere fact that homing pigeons navigate by following human-made roads so rigidly that they sometimes fly around roundabouts before choosing the exit that would lead them to their destinations should be sufficient to show that the duality of “advanced” human intelligence versus “base” animal instinct is delusional, and our fixation on a singular metric of intelligence woefully misguided.13 So when we rely upon a rhetoric that paints pigs as being “as smart as a human toddler,” even as an argument for the ethical treatment of pigs and other animals, we inadvertently perpetuate this human arrogance and the notion that other-than-human animals are comparable to mentally underdeveloped human beings.

Much of this discussion also overlooks the possibility that “higher” (read: more “humanlike”) modes of intelligence are not prerequisites for the experience of and ability to form values and preferences about the world. Thousands of years of social oppression have erroneously conflated our understanding of advanced reasoning capacity with conscious selfhood in our fellow humans as well as other animals. But you don’t have to be smart “like a human” to be able to experience both the outside world and the state of being you.

In 2012, a group of prominent scientists, witnessed by Stephen Hawking, signed the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, confirming that there is no longer doubt that “all mammals and birds, and many other creatures” possess the neurological substrates necessary for consciousness.

Our understanding of not just “basic” or primary consciousness but self-consciousness of an order that constitutes personhood (as it presumably applies only to humans) is ever-evolving. Ironically, modern scientists are beginning to realize that a picture of human self-consciousness, or what our forebears would characterize as the human soul, cannot omit the physical body and our “animal nature,” the very antithesis of our self-definition. Experience of the conscious self is experience of a self with a body, whose functions must be constantly controlled and regulated to be compatible with one’s survival. Selfhood may very well be grounded in the biological mechanisms that we share with other living beings.14

Is there any good reason, then, to believe that other animals aren’t self-aware, or that theirs is a “lower” consciousness? An absence of evidence, in almost all instances due to human error and oversight, must not be taken for evidence of absence. Unsurprisingly, we arrive at the conclusion that we are, in a sense, all beast machines, undoubtedly much to Descartes’ chagrin if he were present to witness this exciting development in scientific discovery. We are all creatures of flesh and blood who act upon the basic drive to stay alive—a characteristic that differentiates animals, human and otherwise, from even the smartest of computers and artificial intelligence. That is what should hold moral weight, not the ability to exercise obscure political rights or pledge allegiance to any given society.

Repeated denial of other-than-human personhood and the subjectivity with which other-than-human animals experience the world and their conscious selves excuses us from facing the question of our moral responsibilities to them. This evasion also explains why the status of the legal person (and personhood in the legal context is in many ways weaker than the popular understanding of the term) has been granted to the Ganges river in India and the Whanganui river in New Zealand Aotearoa, and some constitutions now give nature broad rights,15 when the overwhelming majority of other-than-human animals are still awaiting their turn. This means that humans in different cultures have already started to stretch the boundaries of personhood, even when this contract may be non-reciprocal: rivers aren’t capable of moral behavior, least of all toward humans, nor can they fulfill legal and political responsibilities. (Readers may note the parallel to the reductio ad absurdum argument against legal personhood for other-than-human animals that hinges upon their inability to vote.) Nonetheless, we recognize that the significance certain environmental entities hold in various human populations’ livelihoods grants them a place in moral discussions.

Through language, ways of experiencing the world that are incongruous with the human experience are further invalidated and belittled. We deny the existence of entire realities and repress the very being of the other-than-human victims of human supremacy, such that they are no longer thought of as subjects, singular and irreducible to insensate machines. Like other instruments of social control, language helps to legitimize and cement categories of “human” and “animal” as meaningfully separate from each other, despite the lack of any biological basis for such a division.

As the complexity of other animals continues to surprise us, as we slowly begin to learn that human consciousness is but one of a vast number of possible selves, it’s time to acknowledge that other animals experience life in sometimes vastly different but equally valid ways; that their ways of knowing and being mentally active are not precursors but parallels to our own, and don’t make any of them more or less of a person.

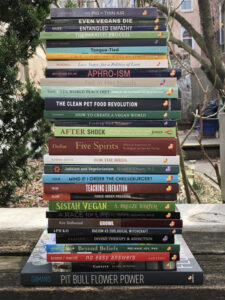

“The article is an excerpt from Tongue-Tied: Breaking the Language Barrier to Animal Liberation by Hanh Nguyen (copyright 2019). It is reproduced with permission of Lantern Publishing & Media.”

Hanh Nguyen Bio:

Hanh Nguyen holds a BA in Sociology from Yale University. Her journey in rethinking human–other animal relationships began when she was an undergraduate, and has since taken her to dozens of colleges and universities across North America, helping thousands of students examine their own perceptions of other-than-human animals. See all books by Hanh Nguyen

Mission:

Our mission is to inform and inspire new generation of global citizens to create a healthy, compassionate, and resilient world for animals and humans alike. Our mission is to inform and inspire new generation of global citizens to create a healthy, compassionate, and resilient world for animals and humans alike.

We are driven by and committed to equity, diversity, nonviolence, and an expanded community of subjects. We publish books, develop content, and promote ideas supportive of veganism, animal rights, humane education, recovery, therapy, and spirituality.

We publish books for all wanting to live with greater depth and commitment to the preservation of the natural world.

.

History:

LPM aims to educate, provide resources for, and amplify a new generation of citizens committed to finding solutions and collaboration. Our goal is to expand the definition of “humane” to one that nurtures, honors, and protects the web of life upon which all species, including our own, depend. LPM aims to educate, provide resources for, and amplify a new generation of citizens committed to finding solutions and collaboration. Our goal is to expand the definition of “humane” to one that nurtures, honors, and protects the web of life upon which all species, including our own, depend.

LPM was founded in 2020 as a 501(c)(3) non-profit to follow and expand on the legacy of Lantern Books—a publishing company started in 1999 on the principles of living with a greater depth and commitment to the preservation of the natural world. Like its predecessor, Lantern Publishing & Media produces books on animal advocacy, veganism, religion, social justice, and psychology and family therapy.

Lantern is dedicated to printing in the United States on recycled paper and saving resources in our day-to-day operations. Our titles are also available as ebooks and audiobooks.

Back to Issue 3

|